by Abbi Hofstede

While we don't need to feel guilty about the past, we can (and should) feel responsible for how the past manifests itself in the present.

It is difficult to know where to begin. I want to say something about how uncomfortable I am with writing about this topic, but my discomfort is nothing in the grand scheme of things, especially when I think about the real beast that is systemic racism.

My first reaction to being asked to write for ICS’s blog was to say no, because I am not the one who we need to listen to right now. As a white Canadian woman of Dutch descent I would feel much more comfortable with doing my own personal work on these issues out of the public eye. The reality is, however, that I am among one of the privileged demographics here at ICS. I grew up going to a CRC church. I ate things like boerenkool and hagelslag. I am steeped in a reformed understanding of Christian education, attending Christian schools my whole life. Since I am in a position of privilege, then, it is not enough to do my own personal work while remaining silent on these issues. In this case, silence would imply assent to the status quo, and that is not okay.

I am not the voice we should be listening to, but I am also not willing to make others do the work for me. For that reason, as a white person, I want to take a moment and recognize that this blog post is intended to engage other white people, as we collectively acknowledge the work we need to do (and the fact that people of colour have not had the privilege to be as unaware of these issues as we are). The reality is that ICS doesn’t have many students of colour, and there are no Black students currently attending. While it is imperative we first and foremost pay attention to and amplify Black voices during this time, we also should not force other people to do the heavy lifting for us.

It is only in recent years that I began to see how deeply systemic racism is ingrained in my experiences of Christian educational institutions (as it is, to varying degrees, in all institutions that have historically been predominantly white). When I stop and think about this reality, I am deeply saddened—not only by my own ignorance, but more importantly by the fact that this systemic racism still persists. Thinking back, I was so unaware of what some of my peers were going through. Because of my privilege, I’ll never fully know all that they experienced, and I lament my lack of understanding to this day.

Recently, I was talking to a friend about the difficulties of navigating this topic. She suggested a really helpful metaphor for conceptualizing systemic racism in an institutional context, one that makes a lot of sense to me as I have spent my summer landscaping and gardening. If we view our institution as a garden, we can think of it as something like this:

ICS’s garden has been nurtured on Anishinaabe, Huron-Wendat, Haudenousaunee, and Mississauga of the Credit First Nations land for over 50 years. Some seeds were brought over from the Netherlands and planted in this soil. These seeds have used the nutrients, as well as the water, sun, and other resources from the land in which they were planted in order to sprout and bear fruit. Many varieties of delicious fruits and vegetables have been grown. Unfortunately, many weeds have sprouted too. Some of these were brought in with the original seeds, and others have popped up over the years. Some existed in the soil when ICS first planted its garden, as the soil had been worked before by a country founded on colonialism. Many of these weeds were not pulled and were allowed to go to seed, producing new generations of weeds that threaten to choke out the other plants.

Systemic racism, in all its manifestations, is one of these pervasive weeds. To continue the gardening metaphor, I would like to propose that those of us who are “insiders” in this tradition need to bear the brunt of the work in uprooting these weeds. We cannot leave this solely to those who have been working for generations, those who face this struggle every day, without any choice in the matter. It is also our responsibility to put in the work. At the same time, we may not be able to recognize some things as weeds. Overtly racist occurrences are a rarity and there are many ways in which racism manifests itself that we may not recognize right away. As Dean pointed out in his post, for example, we might need to call into question just exactly who are the voices that we prioritize here in our classes at ICS.

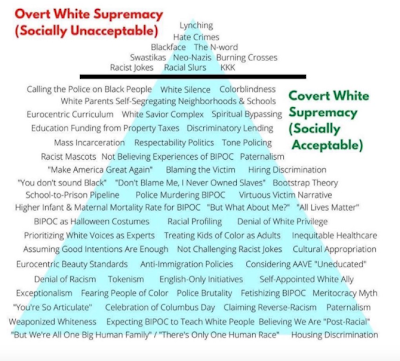

For more examples of how racism manifests itself in many different ways, see the below illustration of a pyramid of white supremacy. This pyramid helps us to see how overt white supremacy builds on these “smaller,” socially acceptable forms of racism and covert white supremacy. While we may recognize the overt things as “bad,” it is sometimes much more difficult to identify the covert forms. This is where we need to listen to Black voices, and the voices of other people of colour, to help us identify those weeds to which we are blind. Then, we—and I’m speaking to white people here—need to put in the work to pull those weeds. As the pyramid illustrates, these covert logics and acts of white supremacy may be buried deep, which means that we might need to dig deep within our own thinking to uncover them.

|

| Source: Safehouse Progressive Alliance for Nonviolence (2005). Adapted by Ellen Tuzzolo (2016); Mary Julia Cooksey Cordero (2019); The Conscious Kid (2020).

|

Recently, I participated in an anti-racism workshop put on by

SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) Toronto, and to prepare we were asked to read an excerpt about the characteristics of white supremacy culture from

Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun (ChangeWork, 2001). Reading this list shook me, if I am being honest. Although at first I didn’t want to admit it (which itself is part of the problem, as we will see), I could immediately see in myself these characteristics of white supremacy culture. Since I have grown up in a culture where whiteness is the norm, this should have been unsurprising. And yet, I was shocked. It was another reminder of how far I as an individual and we as a society have yet to go.

The pyramid can also help illustrate an interesting faultline that often springs up around conversations about race. For some, racism or “being racist” refers only to those things at the top of the pyramid—the overt forms of racism. This can lead to miscommunications in our discussions, with those who hold this view of racism vehemently objecting to admitting their own racism because they view racism as only those things at the top of the pyramid. What the pyramid shows us, however, is that racism takes many different forms. It’s sneaky. It’s embedded in everything from personal attitudes to institutions to government and civil society. This means that you can be racist without intending to be racist—without even knowing it.

Take one example from the pyramid: Eurocentric curriculum. It’s not as if ICS consciously set out to build a Eurocentric curriculum, but it still happened. We come from the Dutch Reformational tradition, so it is natural that a lot of our scholarship is rooted in this area. One of the strengths of this tradition is its deep-seated emphasis on engaging culture and public life. But maybe we need to take a hard look at what culture it is that we are engaging. Too often, the other voices we interact with philosophically are other white voices. How much could our scholarship be enriched if we really made an effort to engage with the voices of people of colour?

During my time at

The King’s University, I once heard a professor describe it like this: there is a difference between guilt and responsibility. While we don’t need to feel guilty about the past, we can (and should) feel responsible for how this past manifests itself in the present. As we have seen from recent events, the reality is that racism is alive and well in our society today. ICS has a responsibility to take a hard look at our own practices as a predominantly white institution. Perhaps we need to question why, after 50 years of existence in one of the most multicultural cities in the world, our student body still doesn’t reflect this. And further, have we ever had one Senior member who was

not white? These questions just barely begin to scratch the surface, and we evidently have much more digging to do.

ICS stewards a rich tradition of Christian scholarship, one that comes out of the Dutch Reformational tradition. There is nothing intrinsically racist about being committed to a tradition per se (although it is worth noting that Abraham Kuyper, among many others, had some very racist ideas).* However, in stewarding this tradition for the future we must be willing and able to critically engage with those parts of our past that are oppressive. We cannot be so committed to a tradition that we fail to recognize our weaknesses alongside our strengths. In the 90s, ICS was a leader in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights. We have done this kind of thing before. And we need to do it again.

In a

recent episode of The Sacred Podcast, Theologian Willie Jennings, in speaking about his new book called

After Whiteness (Eerdmans, 2020), points out that when you ask Western educators: “What image comes to mind when you think of the formation of an educated person?” the almost subconscious answer is a white self-sufficient man, one who embodies what he calls “three demonic virtues: possession, control, and mastery.” In any field, according to Jennings, that person is generally considered the archetype. He illustrates that this image is killing us, leading to pain and suffering in our entire education system, as students and teachers are forced to contort themselves and their experiences to fit into this one very specific box. In place of this image, however, Jennings proposes an alternative by which to steer theological (and really all) Western education: that of Jesus and the crowd. By this he means that the educated person is one who, like Jesus, is able to gather people together—even people who normally would not want to be together. In this view, the sign of being fully formed or educated is that you are able to bring people together through what you do, regardless of your field.

Can we imagine ICS as a place that does this? A place that brings together a diverse cohort of teachers and students who are all committed to learning from one another? Can we uproot barriers to this vision such as Eurocentrism and the prioritizing of white voices so that we can really listen to the voices and insights of people of colour? Can we critically engage our own tradition by listening to scholars who may disagree with us, challenge us, and force us to be and do better? I hope so (otherwise, what are we really doing here?).

ICS has a real opportunity here to consciously embrace this kind of education, and put in the hard work of uprooting the systemic racism in our midst.

** As we continue the process of reforming our academic handbooks and policies this fall, I want to challenge us all to have a look at

the list I mentioned before and identify the areas of white supremacy culture that exist in our midst. As the authors illustrate near the bottom of the linked article:

One of the purposes of listing characteristics of white supremacy culture is to point out how organizations which unconsciously use these characteristics as their norms and standards make it difficult, if not impossible, to open the door to other cultural norms and standards. As a result, many of our organizations, while saying we want to be multicultural, really only allow other people and cultures to come in if they adapt or conform to already existing cultural norms. Being able to identify and name the cultural norms and standards you want is a first step to making room for a truly multicultural organization.

If we want to be a place that brings people together, then, we need to de-centre whiteness to ensure that other voices truly feel welcomed and that we have the ability to hear them.

It seems to me that it is more than time to put the old archetype of white mastery fully and completely to rest, just like a noxious weed needs to be thrown into the trash. This means, among other things, listening to different voices—in our classes and in the broader life of the institution. Nothing about this process will be simple or easy. It is going to involve making mistakes, let’s just acknowledge that. As a white person, I am blind to many of those weeds that are perhaps all the more insidious for just looking like “the way things are.” I am going to need direction and guidance, and I am going to have to do a whole lot more learning from people who are different from me. This blog series is a start, as we will be first lamenting our complicity in these abuses and then looking to how we can grow. In a future post, we hope to have a curated list of resources to help us learn and grow, to help us as we put in the work and begin the process, (so stay tuned!).

The old ideals have deep roots. But I am ready to grab a shovel and start digging. I hope you will join me.

- - - - -

** It will be important to recognize too that there are some things on this list that ICS has already consciously engaged with, and as a result these areas may not need as much work. There are many things we can (and should) celebrate about the culture of ICS, for example, its participatory governance structure that invites Junior and Senior Members alike into the process of governing the institution. At the same time, the point of this blog series is to draw attention to and lament the areas where we have failed in the past, which is why I have chosen here to focus on these areas.

- - - - -